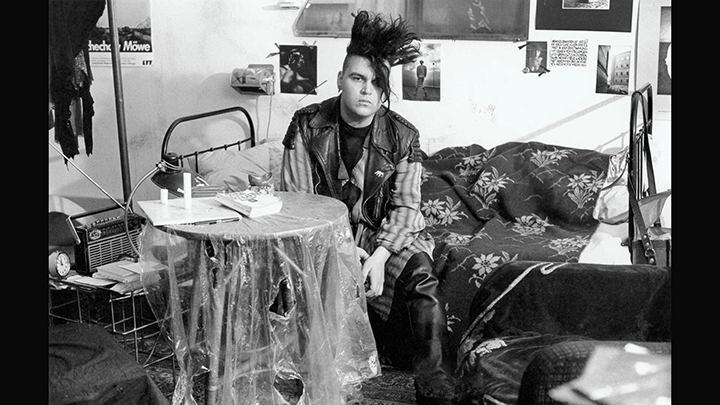

“I always imagine that when I depart from this life, I’ll enter an intermediate circle of hell, like in a Hieronymus Bosch painting. I’ll have to knock repeatedly. And they’ll say, ‘No, Not you!’ ” jokes Sven Marquardt – an iconic no-man that can be met at the door of Berghain. “Berlin Bouncer” is a documentary telling a story of three legendary doormen – Sven, Smiley, and Frank Künster – who share their thoughts about constantly changing techno capital and their relationship with this city. I met with a director David Dietl at CPH:DOX, a 16th international documentary film festival in Copenhagen, to talk about the film and these three picky characters that take selection process more seriously than it might look.

How did you come up with an idea to build a documentary around the legendary guardians of Berlin parties?

Actually, I was thinking about doing a feature film which is set in Berlin, but everything I came up with wasn’t enough to build the feature film around it. I just started asking myself, “What is it, really, all about and where the most exciting people are?”

I studied at the Berlin Film School and I was out and about to the Berlin nightlife. Over those years there were three bouncers that I’ve always met at different clubs who kind of stayed in my head because they were more than just bouncers they were like intriguing personalities. I did some research, and I found out that they have interesting background stories and all of them now in their fifties and they’re still doing the job. I thought it has to be addictive in some way and I wanted to know who they are and what they do if they’re not standing at the door of these clubs.

I would imagine that it was also quite unexpected for Sven, Smiley, and Frank to get this offer. Was it hard to convince them to be featured in the film?

I approached them through different means. Smiley also gives security service for the Berlin Film Festival, so I met him there at a party and just chatted him up and got his number and said we should meet and talk. And Frank, the other one, I knew from before, so he was pretty easy to convince.

I knew that for this film I would also need Sven Marquardt; otherwise, people will be disappointed. I also knew that it wouldn’t be easy to contact him and to persuade. So, I went through a DJ friend of mine – Marcel Dettmann – who also plays at Berghain – and asked him to set up a meeting so that he knew that I was OK to talk with… Basically, we got along pretty well; we found out that we have the same sense of humour. At that time, Sven just had done his autobiography, and he had enough of publicity right now and then, and he didn’t want more. But as he is also a photographer and not only a bouncer, I told him that I want to, you know, look behind his image. Then he said, “let’s give it a shot!” And this started over four years ago, somewhere in 2014.

“Berlin Bouncer” was the first documentary for you; what was the reason that made you challenge yourself and work on the non-fictional piece? Would you agree that for storytellers it is important not to restrain themselves in one genre?

Absolutely. As a filmmaker, you decide which kind of film suits the topic. The first film I made was a mix of documentaries – it was a mockumentary. And in this case, as I said, I wanted to do a feature film, but real life and real people that I’ve found could tell the story of Berlin and its nightlife way better. And yes, it has its ups and downs; You get a lot from a documentary: the people, their stories that often are better than anything you could have come up with. But then, again, you can’t force them into the way that you or story want them to be. And obviously, I had different ideas for this film, but I always had to adapt what I got and what they allowed me to see. And then at a certain point, I knew that I wouldn’t get behind certain things which, at first, was a little bit depressing, but again – I think the film tells a lot about what is not said and what they don’t want to talk about. It was a significant learning experience, and I believe for both ways – you can learn a lot as a feature film director from doing documentaries and the other way around.

Talking about these three characters, since you were around for quite some time. Did you notice some similarities in their personalities?

Not at all! They’re entirely different in their approach of how to do their job. Maybe one similarity might be that for them doing the selection at the door is something they take very seriously. And they really like to do it! They have a perfect sensibility for people that fit the party. There are no real rules for this yet I think it’s a gut feeling. Obviously, people who don’t get in are always disappointed. Yet for the bouncers, it is crucial to make sure that party is as best as it can be because a person inside is not just standing and looking at others or having some prejudices but that there are freedom and only good souls.

So what ties do you have with Berlin city?

I was born in the States, grew up in Munich and came to Berlin to study at the film school when I was 21. And the film school took me some time because nightlife in Berlin at that point was more interesting than studying. So, I lived in Berlin for 15 years, and now, I moved back to Munich. This is also some kind of a farewell film for Berlin and for that time which I wouldn’t necessarily say that is over; it’s just always changing. Berlin is reinventing itself, and the nightlife is reinventing itself too. I just have the feeling that this part where I was really into the nightlife, and where these three bouncers over the last 15-20 years played the main role is slowly over… And the new time is beginning. So that’s also something the film is showing.

“Berlin Bouncer” aims to reflect these changes in the city after the fall of the wall in terms of freedom and expression. What changes do you see today in Berlin’s party scene?

Today, Berlin is still not as judgmental as many other places in the world, and it’s also affordable. That’s why a lot of people can live their lives and do things as they want here. When I came to Berlin in 2001 everybody said, “You completely missed out on the 90s. It was the best time, the wall went down, everything was crazy and free, but it’s over now.“ Honestly, I didn’t have the feeling I missed out on everything because these years from 2000 to 2010 were also very vibrant; then also for the friends that came out in 2011 or later I was telling, “Oh you missed out on the good time! ”

I guess, you always have the feeling that time is over, but I think that Berlin is capable of reinventing itself. Today, I would say that nightlife is more commercial and it’s also more touristic than it used to be before. The greatest thing in the 90s was that a country that was separated and the city that was separated grew together basically in this club scene. And as Sven says in the film, “You get the feeling that the city was most reunited when people were most reunited; when they were partying together because no one asked where you are from, and that didn’t play a role at all.”

Do you think that there is a side of Berlin that will never be experienced by tourists?

No, I believe that as a tourist one has a chance to fully experience Berlin because it’s open and doesn’t hide anything from its visitors. But I think since Berliners experience the same things as tourists, they feel like “Why are we not having something that they can’t see?” So, it’s more the contrary. It’s still inclusive, and I think that it always used to be. It used to be East and West Germany, and now it’s the whole world that’s coming together, celebrating and partying.

As you mentioned yourself, partying in Berlin became a tourist thing. Do you think that this might affect the parties itself in the future?

Probably it will. I hope it won’t, but it also has a positive aspect – the politicians in Berlin have realized that the whole party scene is a major tourist attraction and it’s also a major industry. Now, when new places are opening the city helps clubs, for example, to prolong their lease or stay in different locations that they usually would just pull-down and build high rise buildings instead. And now they know that Berlin has this sense and it’s something that keeps the scene going.

Does this movie please only fans of club-scene and techno culture? What kind of audience did you have in mind while creating this piece?

First of all, I try not to have such a big audience expectation in my mind. I try to make the film that I’m interested in and hope someone else will also find in attractive. It’s a costly experiment though. This film is not that much about the party scene, and although it tells us about the history of Berlin from a divided city to the party town of today, it’s a personal film about three men. About the men that are growing old in this job, and also the question that I ask each of them, “Where is it going. How long can you still do this job and where is your life going to after?”

How did Sven, Smiley, and Frank receive the movie?

I showed them the film before the premiere at the Berlin Film Festival because they trusted me in making it. I was a little bit anxious about how they would take it, to be honest. At first, I thought that they would oppose to many more things than they actually did. It is also interesting because if you see the film, I believe that you will say, “How would they ever say this is OK to show it.” But then it is all about self-perception; I showed them in the way they see themselves and even if that’s not always just positive – it’s true. So, I tried to be as truthful as I could. I interviewed a lot of other people for this film too, and at the end of the editing process, I decided I would only let the three of them talk. All the voiceovers where I would comment on what was happening and so on – I just left that out because I thought it’s much more interesting only to hear them… And as I said, through what they don’t say and don’t want to talk about, one can learn a lot. And that’s all in the film. And they didn’t oppose. I am not sure if they would still do it that way, but now the film is out, there’s no way back!

So, it seems like everything went way better than you were expecting.

Well, not really. It was just a very long process, there were moments where they, especially Sven, called me and said, “I’m out of this project!” Through these ups and downs, we kind of lost each other and found each other again.

Thanks to CPH:DOX for this exceptional opportunity of meeting great talents from all over the world. See you next year!

The interview was originally published in ‘SwO street’ No. 33 (www.swo.lt/swo-street-nr-33).