The Frist Art Museum presents On the Horizon: Contemporary Cuban Art from the Pérez Art Museum Miami, an exhibition that explores the diverse cultural and political landscapes of Cuba and its diaspora through the paintings, photographs, sculptures, videos, and installations of fifty artists. Drawn from one of the largest public collections of Cuban art in the United States, On the Horizon will be on view in the Frist’s Ingram Gallery from January 28 through May 1, 2022.

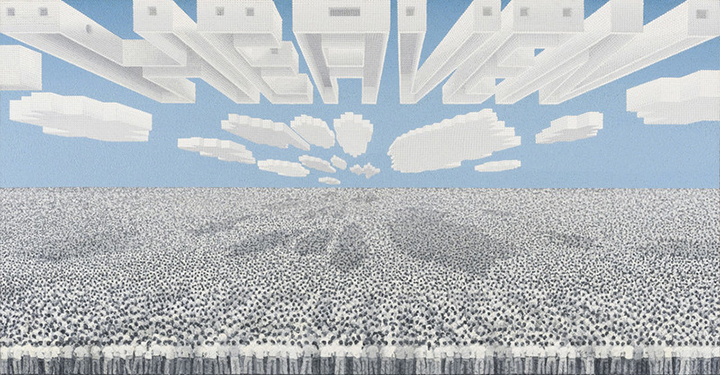

René Francisco. Heaven, 2007. Acrylic on canvas, 49 x 95 in. Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, gift of Jorge M. Pérez. Photo – René Francisco ©

Featuring approximately seventy works by Cuban artists of multiple generations, the exhibition inspires dialogue regarding the physical, social, and political landscape of the island and its diaspora. Artists include Yoan Capote, Los Carpinteros, Teresita Fernández, Enrique Martinez-Celaya, and Zilia Sánchez. Vanderbilt University art professor María Magdalena Campos-Pons, who won the prestigious Pérez Prize in 2021 in honour of her powerful explorations of history, race, and culture, has two large triptychs in the exhibition.

The horizon line functions as a motif and symbol of personal desire, existential longing, or geographical containment throughout the exhibition—while always visible and alluring, it remains perpetually distant and unattainable. Works in the exhibition demonstrate how artists can weave political commentary into their practices, providing insight into the sophistication of creative expression that is possible even in an authoritarian system. Those artists working in exile offer a different perspective, exploring memories, political contrasts, and personal identity through the lens of displacement. “Because of the strained history of Cuba-US relations and the current unrest in Cuba, especially in artistic and intellectual circles, the exhibition’s timeliness cannot be overstated,” says Frist Art Museum chief curator Mark Scala. “In these works, guests will see hardship and humour, despair and hopefulness, spirituality and political critique.”

Organized thematically, three sections explore various meanings and associations related to the horizon. The first section, Internal Landscapes, begins with works that find emotional power in seascapes, landscapes and imagery relating to Afro-Cuban experience. In Yoan Capote’s painting Island (see-escape) (2010), a perilous sea made of fishhooks appears like a prison wall and is a reminder of the ideological barrier separating communist Cuba from the U.S. Threats loom from every direction in Luis Cruz Azaceta’s Caught (1993), in which a terrified and demonized man is stuck with no good options—only rough water, imprisonment by the Cuban government for attempting to leave, or interception and return by U.S. officials.

The next section, Abstracting History, examines abstraction employed as both a formalist strategy and a tool for critical and subversive thought. Geometric abstraction, as seen in works by Waldo Díaz-Balart, José Ángel Rosabal, Zilia Sánchez, and others, demonstrates how cosmopolitan Cubans of the 1950s and early ’60s embraced modernist European styles such as neoplasticism, constructivism and suprematism. “Such styles quickly fell from favour in the early years of the Castro regime, when art with a clear social message was officially preferred, as it had been in the Soviet Union since the rule of Josef Stalin,” said Scala. Despite the government’s position, artists such as Glenda León and Reynier Leyva Novo continued to develop personal approaches, creating social or political critiques as well as poetic abstractions.

The artworks in the final section, Domestic Anxieties, relate to the anxieties and stresses felt today by many Cubans on the island and elsewhere. René Francisco’s seemingly utopian image Heaven (2007) offers an ironic commentary on collectivism, in which individuality and personal freedoms are subordinated to the greater dictates of society. The word heaven hovers over a crowd like giant propaganda assuring them of how good their lives are. Upon closer inspection, however, prison bars are visible in the letters, suggesting that the masses may face imprisonment if they do not accept this vision of communal bliss.

“Prompting a dialogue about Cuba and its diaspora, the artists in the exhibition connect their own experiences with historical, political, and psychological realities to create works that can resonate with anyone who grapples with questions of freedom, identity, and displacement,” says Scala.